How engineering and technical innovation can meet the challenge of feeding a growing global population

There are always plenty more fish in the sea, so the saying goes. Turns out it isn’t necessarily so true anymore.

Over-fishing, poor management of fish stocks and the impact of a changing climate means that we must now look increasingly for new ways of satisfying the global demand for fish as a sustainable source of food. The development of the Floating Ponds urban farm concept – a radical systems based design incorporating innovative engineering and technology – holds the potential to turn the dream of efficient, self-sustaining food production into a reality.

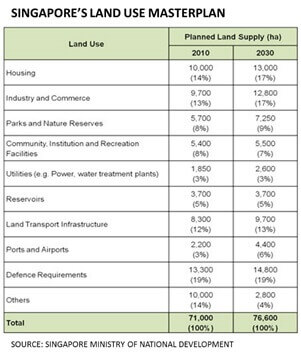

The global population is becoming rapidly urbanised, with the United Nations’ predicting that some two thirds of the global population – around 6 billion people and rising – will be jostling for space in the cities by 2050. Oceans and farmlands are falling short of meeting our food demands. Climate changes are fast rendering farming uneconomic and untenable; and those which still are, are being gobbled up by sprawling metropolitan areas for housing, infrastructure, or commercial needs.

Thus our ability to feed ourselves is and will be challenged by the need to provide for housing, infrastructure, transportation, employment, education and all other basic requirements in competing for the strained limited resources we have.

Sustaining a sustainable healthy food source for these dense urban areas is a vital challenge

Rethinking food production:

Surbana Jurong is rising to this challenge with the Floating Ponds high-intensity urban farming concept. The vertically stacked fish raceways help to multiply the production capacity of any available space, and not just land; whilst its inherent self-sustaining, closed-loop farming eco-system optimises the use of resources – water, nutrients and energy.

The result is an ecologically sustainable farming model which is modular, scalable and replicable.

Currently Singapore imports some 92% of the fish consumed locally. Rising concerns over the sourcing of fish has switched focus towards ways to improve local production and increase the sustainability and reliability of the food supply.

Land based fish farms are not in themselves a new idea. Landlocked regions or high-density urban development without access to conventional fish farming have been developing such food sources. However, these traditional facilities are resource hungry and consume enormous quantities of water, energy, and nutrients to produce quality fish products. The Floating Ponds model sets out to transform this existing model.

Systems Thinking to Close the Loop:

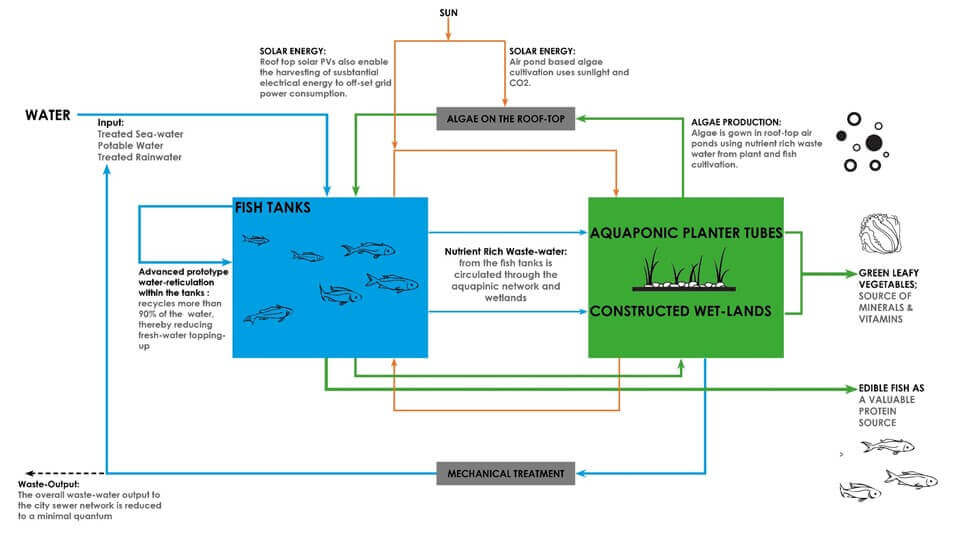

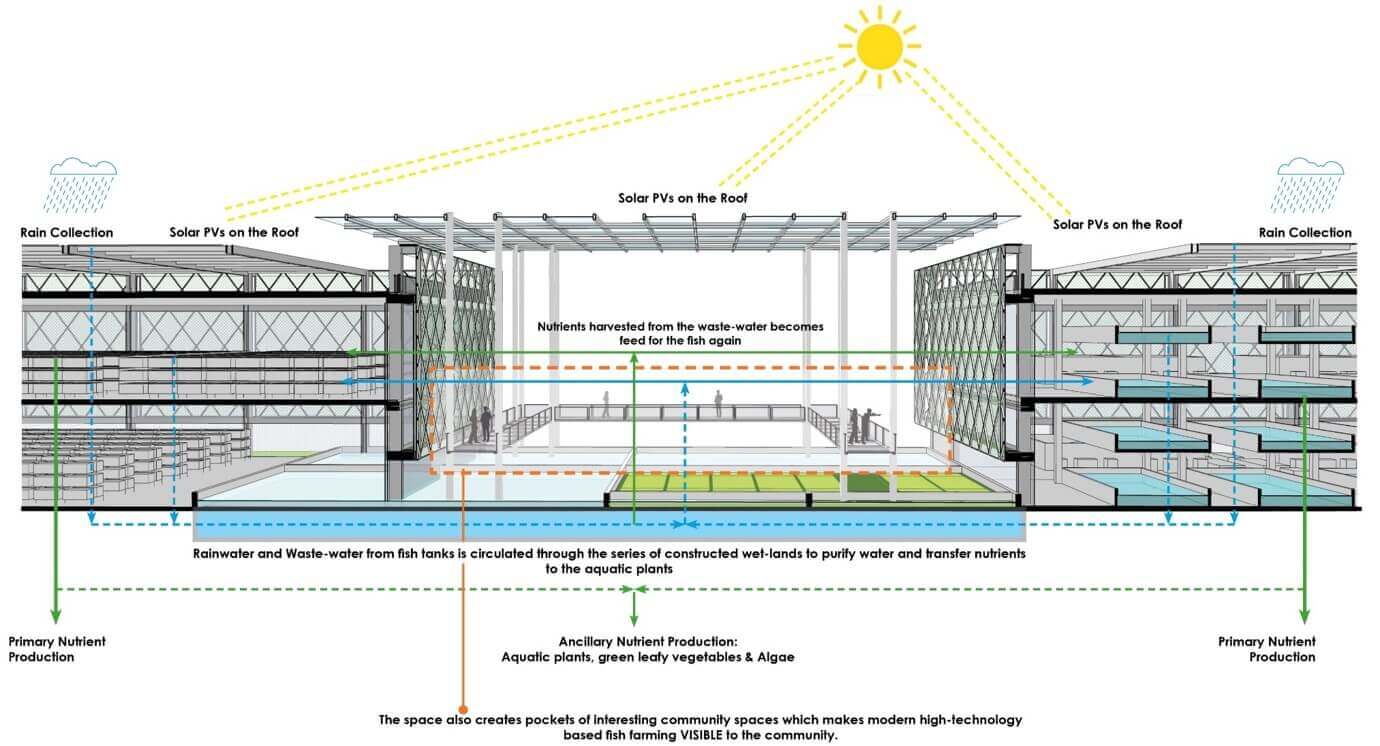

The vision for urban fish farming is founded on a comprehensive systems level integration of the three primary systems engaged by the farm – water, nutrients and energy. The design and architecture of the farm works towards enabling flows and exchanges amongst the three systems. The concept employs a vertical stacking of water raceways for fish farming which helps to relieve space for the environmental systems needed to create these systems flows and exchanges to ensure a closed loop ecosystem.

Water reuse:

The role of water is paramount to this project. Traditional fish farms consume large volumes of water in a linear flow set-up, rendering significant volume to be discharged into the sewers as waste. Together with it, vital residual nutrients are washed away as well.

In Floating Ponds, it is the planned flow of water which creates the medium for the systemic exchanges to take place.

Expunged waste water from the fish tanks is treated via a specially constructed wetland system to enable natural cleaning as bacteria and aquatic plants feed on the organic waste while the drainage actively captures rainwater. Treated water can be re-used for several non-potable uses or re-circulated back into the fish tanks. Alternatively, the nutrient-rich water from the fish farm can be fed into a hydroponic system to sustain the production of vast quantities of green leafy vegetables. Bio-swales enhance the water system by treating and capturing surface run-off thus reducing demand for clean potable water in the fish tanks.

Such concerted efforts can reduce the volume of water being discharged out from the site into the sewer system.

Nutrients:

In addition to the primary nutrient being nurtured in the form of fishes, the aquatic plants in the wetlands become an essential ancillary source of nutrients. They help to close the nutrient loop as a certain quantum of them is processed back to become feed for the fish.

Furthermore, micro-algae are cultivated using the nutrient laden waste water as feed for the fish. Algae are also used to condition the sea-water which is also used as a source of topping up.

Hydroponics further adds to the production capacity of green leafy vegetables by directly using the nutrient rich waste water from the fish raceways.

Energy:

The roof structures covering fish farming areas of the Floating Ponds provide a perfect platform for the use of photovoltaic panels capable of generating enough energy to offset significant portion of the consumption demands. Algae, grown in transparent tubes and pumped with waste water and a lot of CO2, is capable of producing bio-fuel in the presence of sunlight. This is a technology which requires more research and development but clearly holds future potential as demonstrated in projects across the world.

Besides the conscious design decisions to incorporate passive design features, the overall energy balance can be significantly enhanced by efficient and innovative technologies for spaces such as labs, offices, cold storage which inherently tend to consume more energy. Technologies such as passive displacement ventilation, radiant cooling, the use of heat recovery systems are being considered together with the use of fan assisted ventilation to improve thermal comfort at higher supply air and room temperature.

Creating a modular system that meets the needs of the community:

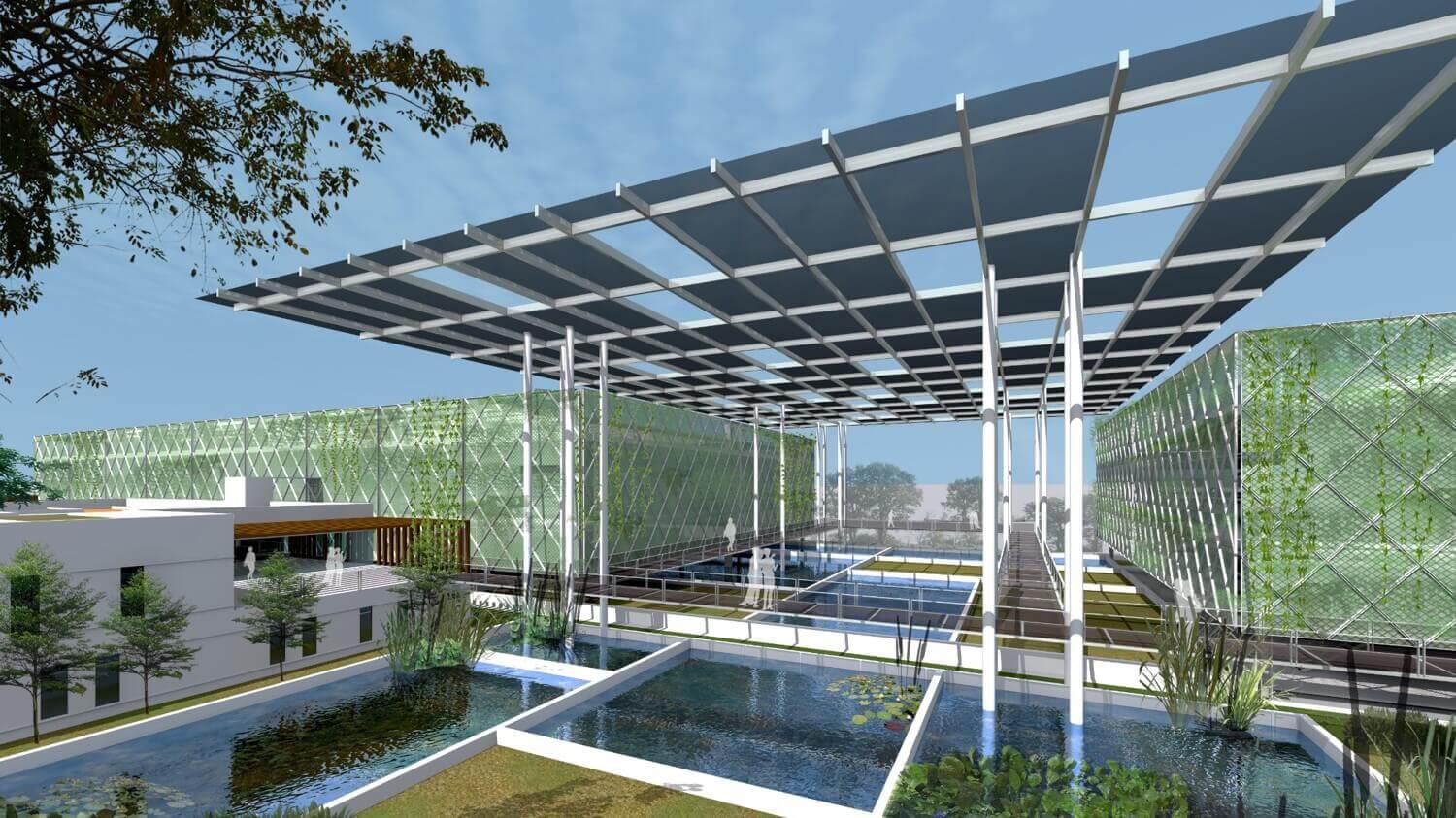

By rethinking the factory fish farm model, the team has developed an integrated, self-contained farming ecosystem, placing local food sufficiency and resilience for the local community at its heart. To be successful, it is imperative that the farming and food production process is visible and accessible to garner community interest and attract engagement.

As such the central space above and around the constructed wetlands attempts to create a space to anchor that community engagement – both spatially by drawing visitors in but also functionally by providing a useful and attractive recreation area. While by being modular and scalable, the Floating Ponds typology makes itself flexible and adaptable to any available urban space, ranging from a park space, to un-used roof space and to even community spaces within larger commercial developments.

In doing so, Floating Ponds can not only make a small pocket of urban space significantly productive by producing high-value food fish, but can also enhance the surrounding ecology and generate a vibrant community hub with farming activities.

A design that adds to the urban environment:

With this initiation in Singapore and in the face of the global challenges of urbanization and food production, high-tech, systems based and resource efficient facilities such as the Floating Ponds will soon start to transform food production around the world.

Fundamentally, the Floating Ponds concept will create a new urban typology; taking high-value food production out of isolated and secluded land-based farms and placing them into the heart of high-density urban cores, as inclusive elements of the social and economic function of the city.

Image caption: Systems Map

Image caption: Planning for a closed-loop vertical fish farm which allows for systemic flows and exchanges

Image caption: Functioning prototype built to test the vertical stacking and the water reticulation system

Image caption: Elevated visitor / community spaces suspended above the integral blue-green spaces

连接